In this scattershot series, we’ll be delving “too greedily and too deep,” prying gems out of the glorious rough that is the extended legendarium of Tolkien’s world. This includes drawing on The Lord of the Rings itself, The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, and the History of Middle-earth (or HoME) books.

By and large, J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium hammers into us—as if on Aulë’s own forge—the fact that when Men kick the can, they don’t come back. Quite unlike their Elven counterparts, for whom “no sickness or pestilence brought death,” Men shuffle off their mortal coils with ease. In our present time, in the real world, where illness is often in the forefront of the news, I’ve personally found that it’s easier than ever to think about the death that all Men must face.

But even in Middle-earth, Tolkien’s secondary world, you sometimes have to wonder: was it supposed to be like this? Well, YES, insist the Elves and even the oft-omniscient narrator of these stories. Ahhh! But that’s not how Adanel—mortal Wise-woman of the First Age—tells it!

So wait, who’s this Adanel? I sure would like to know more myself.

Well, first, she’s not in the published Silmarillion (1977) at all, because she and her tale—like much of the material contained in the History of Middle-earth series—are not part of the “most coherent and internally self-consistent narrative” that was Christopher Tolkien’s priority in the late 1970s. Second, we only know Adanel and her tale, well, secondhand. Which is just something we have to accept that Tolkien liked to do. (I’m talking to you, entire siege of Isengard.) Truly, some of the most fun dialogue in The Lord of the Rings is simply quoted by someone else who’d been there. For example:

“Radagast the Brown!” laughed Saruman, and he no longer concealed his scorn. “Radagast the Bird-tamer! Radagast the Simple! Radagast the Fool!”

That’s right. In “The Council of Elrond,” we’re really just getting Gandalf doing his best Saruman impression for the gathered assembly. I like to imagine he’s standing stiffly and arching his eyebrows in classic Christopher Lee fashion. Who doesn’t enjoy some good Maia-on-Maia mimicry?

Sorry, where was I? Oh yes, Adanel. Adanel is a Wise-woman of the House of Marach (later known as the House of Hador), one of the three great clans of the Edain (a.k.a. the Elf-friends) that settled in Beleriand in the First Age. Who also happen to be the ancestors of the Númenóreans.

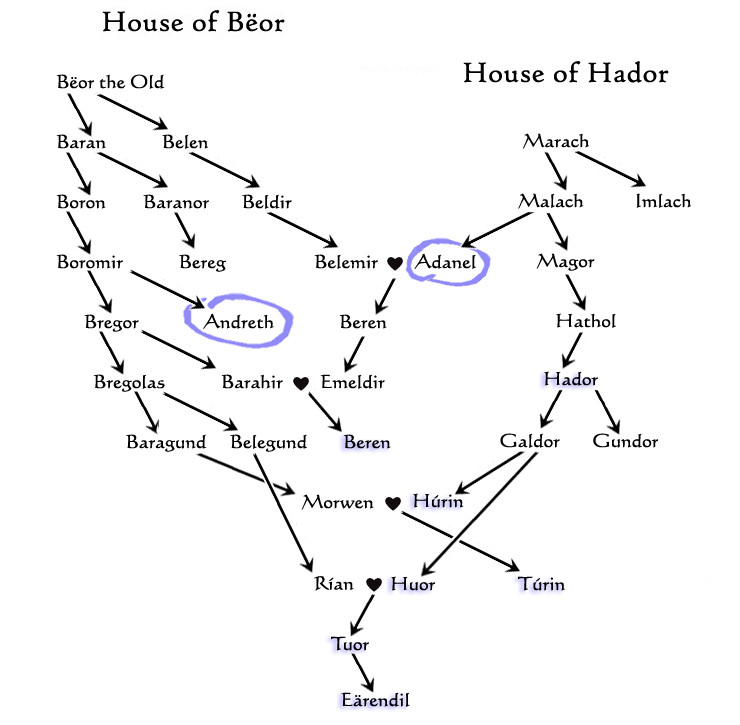

Now, the House of Hador specifically produces some of the A-list heroes of the First Age, including Hador (obviously), Húrin, and Túrin, all of whom Elrond cites to Frodo in The Fellowship of the Ring. Now, in one account, Adanel is the great-grandmother of Beren (of ‘and Lúthien’ fame). But she’s explicitly a friend of Andreth of the House of Bëor, another Wise-woman among Men. Which means both women are lore-masters of their people: Scholars, historians, know-it-alls. Though they’re friends, they’re also essentially distant in-laws; Adanel was probably like the cool, sagacious aunt to the younger Andreth.

And as shown in the non-comprehensive chart below, the people of both Hador and Bëor were not only friendly with one another, they got hitched in a few important places in the family tree.

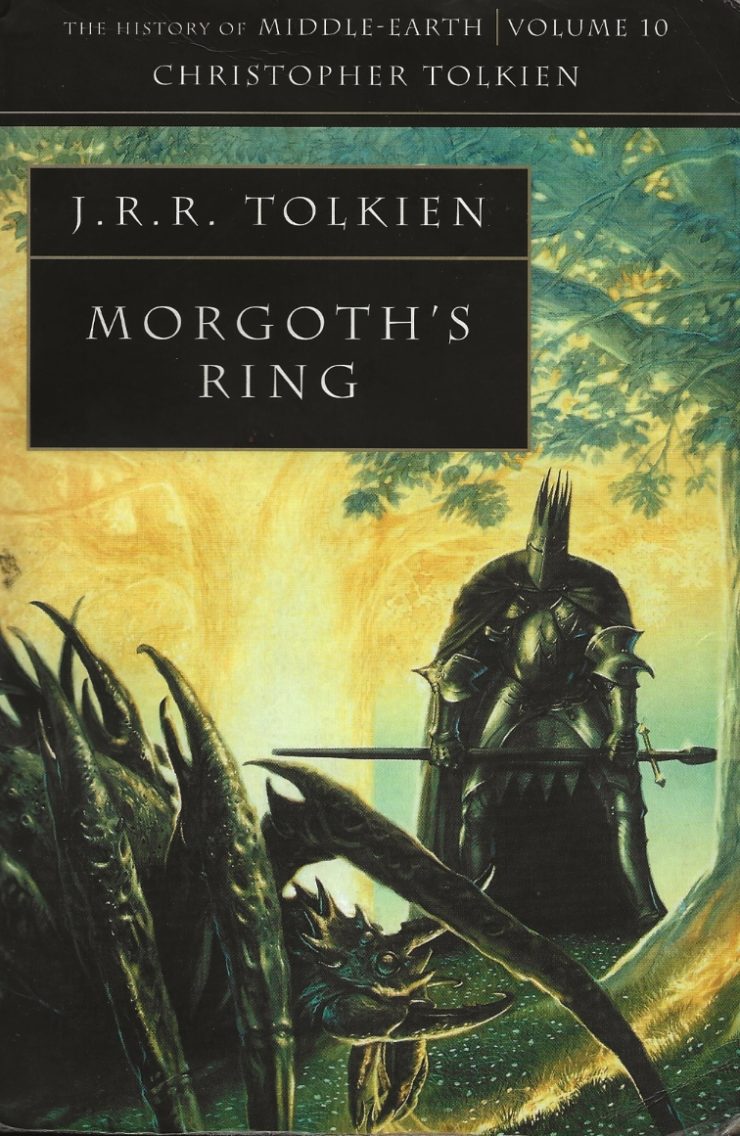

In my last Delving article, I talked much about Andreth and her starring role in the Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth (or the ‘Debate of Finrod and Andreth’), which is a conversation Christopher Tolkien included in volume 10 of the History of Middle-earth, Morgoth’s Ring. It centers on the preoccupation mortals have with death. (Understandably!)

Whether death was part of the plan for Mankind or simply had it foisted upon them (as Andreth asserts), they do have to deal with it. They fear it, they succumb to it, they suffer over it. Especially for those who love or at least consort with Elves—who don’t appear to physically age and probably don’t even get hangnails—death is front and center. Death is a hunter to Men. An affront! Andreth was clear on that point, and who can blame her?

Tolkien was fond of a particular quote by French writer, philosopher, feminist, and activist Simone de Beauvoir, and was even filmed reading it aloud to an interviewer (and which just happens to be sampled at the tail-end of this excellent song by the Dutch rock band The Gathering):

There is no such thing as a natural death: nothing that happens to a man is ever natural, since his presence calls the world into question. All men must die: but for every man his death is an accident and, even if he knows it and consents to it, an unjustifiable violation.

The words are de Beauvoir’s, but Tolkien goes on to call them the “keyspring” of The Lord of the Rings. And when you consider the whole of the larger legendarium—that is, The Silmarillion and beyond—it’s nothing short of foundational. No, it’s not only about death; it’s also about consolation and recovery, free will, and the search for hope in the face of despair.

Still, death and mortality are clear and present factors in The Lord of the Rings. By the end of the Third Age of Middle-earth, Morgoth, the great instigator and the cause of so much death and misery, had already been ousted. He’d been shown the door—literally kicked out of the solar system—by his former peers.

But what a mess he’d left behind for the Children of Ilúvatar to fuss over, right?

In fact, here are some relevant glossary terms for this discussion:

- Ainur — The Holy Ones, the “offspring” of Ilúvatar’s thought. The beings that joined in the Music of creation, and included those who would become categorizes as the Valar and the Maiar.

- Aman — The continent west across the Great Sea from Middle-earth; contains Valinor, the home of the Valar and where a sizable percentage of the Elves have gone.

- Arda — The world (little “w”), which includes the Earth, the seas, skies, and even the firmament around them (the planet and its immediate celestial surroundings).

- Arda Marred — The version of Arda that is, as a consequence of Melkor’s meddling, not precisely the version of Arda that was meant to be.

- Children of Ilúvatar — Both Elves and Men. Biologically, these two races are of the same “species” and as such can “produce fertile offspring,” but the relationship between their respective spirits and bodies mark the greatest distinction between the two. It may be said that Dwarves are “adopted” Children of Ilúvatar.

- Eä — The World (big “w”), the entire universe itself, of which Arda is but a part.

- Eldar — A word generally synonymous with Elves. Technically, it doesn’t apply to those Elves way back in the beginning who opted to stay where they were and not get factored into any of its recorded history. Those are the Avari, the Unwilling, and they’re the one group of Elves excluded when Eldar are mentioned.

- Hildórien — A land in the far east of Middle-earth where Men first awoke in the world.

- Ilúvatar — Eru, The One, the singular god of Tolkien’s monotheistic legendarium.

- Maiar — Powerful spirits that were around before Arda itself. They are of a lesser order than the Valar, but some are nearly as mighty. Gandalf, Sauron, and Balrogs are all Maiar.

- Men — Humans, men and women both.

- Middle-earth — The massive continent where most of the stories in the legendarium take place. Contains regions like Eriador and Rhovanion. Beleriand once formed its northwestern corner.

- Melkor / Morgoth — The Enemy, the original Dark Lord and fomenter of all evil. Formerly the mightiest of the Ainur.

- Valar — The “agents and vice-gerents” of Eru, the upper echelon of spiritual beings, set above the Maiar, and established by Ilúvatar to shape and govern Arda.

Right, so the Firstborn are the Elves, and their heyday has passed. Most have already left Middle-earth for the deathless shores of Aman or Tol Eressëa (together known as the Undying Lands). Those who haven’t are either fishing for their keys and heading out the door toward the Grey Havens or they’re sticking around just a wee bit longer to play some final role in the resistance against Sauron.

Oh yes, Sauron: president emeritus of assholery in the Second and Third Ages, inheritor of his old boss’s legacy, the Maia who pulled that shit with the Rings of Power and has been steadily growing back his strength since Isildur failed to destroy the Dark Lord’s favorite bauble.

Now, the Secondborn of the Children of Ilúvatar, mortal Men, can’t just bugger off. They’ve only got three choices concerning the threat of Sauron.

- Resist . . . like the good guys do.

- Despair of his inevitable-seeming triumph . . . like Denethor.

- Throw in with him . . . which many do, like the Easterlings and the Haradrim, whether they’ve done so willingly or by coercion (probably a mix of both).

Bottom line is, like Hobbits and Dwarves, Men have no option to escape their peril while still alive. They cannot sail into the West; there is no Blessed Realm to receive them, no home base that the Dark Lord cannot eventually overcome. Yet—and this is the crazy thing—Elves maintain that Men have a destiny both within the world and without. On the one hand, the fall of Sauron will mark the Dominion of Men for Middle-earth . . . yet, when they die, no matter the state of things, they will leave that Dominion entirely and go beyond the Circles of the World, never to return. What a weird state to be in! Middle-earth is a revolving door for us, yet we’re meant to be in charge?

So, let’s back up and see how we got here. In Morgoth’s Ring, Tolkien presents a kind of “what if” version of the dawn of Mankind in the Tale of Adanel. This occupies a nebulous place in the legendarium, in that we can’t get reliable eyes on it—and possibly that was intentional. Even the Athrabeth wasn’t neatly tied into his retconned writings (it presented at least one continuity problem), and the Tale of Adanel is nested even deeper in that uncertainty. The bottom line is, Tolkien only noodled around with the true nature of Men and didn’t get around to putting a fine point on it. And maybe that’s for the best. If we learn too much, it’ll be demystified. Myth-busted. And Tolkien was all about myth.

But in the later years of his life, he was thinking a lot more about the souls of his creations (even Orcs, the topic of another article to come), and he did so, it seems, to try to make his secondary world more compatible with his own Catholic beliefs. He explored some of these diegetically, in-world, not just in treatise form. Finrod’s debate with Andreth is a prime example, since he set it during a specific moment in time—before Morgoth breaks from his confinement in Angband and kickstarts the incremental defeats of the Elves of the First Age.

Tolkien really did choose a very interesting point in time for his Athrabeth, too. There was so much more history about to unfold that would have informed a discussion like Finrod and Andreth’s. Imagine if he’d written a second debate about death, one between a different High Elf and another Wise-woman or man, except placed sometime after the rise and fall of Númenor in the Second Age—after the most gifted group of Men were soundly punished for trying to seize immortality from the Valar by force. Oh yeah, and after the world went global and became more like the Earth we know. Talk about having new context and new information, to discuss. Talk about revising beliefs!

Sadly, the Athrabeth Galadriel ah Elendil is just something I’ll have to pretend happened.

The truth is, we can only read about Tolkien’s deeper insights as unrefined possibilities via the History of Middle-earth series that his son curated for us. Again, these are the essays and stories that Tolkien hadn’t fully polished and so cannot be neatly dropped in among better-known works.

So yes, one such insight is the Tale of Adanel. It’s the apocryphal Disaster (capital D!) of Men, an event analogous to the Kinslaying among the Elves. Quite possibly it’s just a parable that Men cling to, to try to make their fate more comprehensible. It’s a short tale dropped at the end of the Athrabeth, and it’s told in the voice of Andreth as she relays the story that her friend told her. Remember, this is a narrative specifically not shared with the Elves at large; Finrod is extra special for hearing this—if even he got to—and so are we.

In this tale, it’s implied that Morgoth did, in fact, sneak out of his bunker in Angband at some point specifically to mess with Men soon after their awakening. There is some small but significant support for this even in The Silmarillion. From the chapter “The Flight of the Noldor,” where we’re told that Morgoth, forever trapped in the body of “a dark Lord, tall and terrible,” settles in Angband with his newly fashioned crown set with stolen Silmarils:

Never but once only did he depart for a while secretly from his domain in the North; seldom indeed did he leave the deep places of his fortress, but governed his armies from his northern throne.

Secretly—that’s the key word.

Then, in “Of the Coming of Men Into the West”:

But it was said afterwards among the Eldar that when Men awoke in Hildórien at the rising of the Sun the spies of Morgoth were watchful, and tidings were soon brought to him; and this seemed to him so great a matter that secretly under shadow he himself departed from Angband, and went forth into Middle-earth, leaving Sauron the command of the War. Of his dealings with Men (as the shadow of the Kinslaying and the Doom of Mandos lay upon the Noldor) they perceived clearly even in the people of the Elf-friends whom they first knew.

Armed with all this, let’s jump out of The Silmarillion and back into Morgoth’s Ring. Here we find Finrod, a Noldorin king (and the best Elf ever), imploring his mortal friend Andreth to tell him the story that’s apparently only ever told among Men. A story about how and why death was imposed on Men, as they believe. Throughout her debate with Finrod, Andreth maintained that Men were not mortal from the get-go, but were made that way only after the fact as a curse. Which is contrary to pretty much everywhere else the fate of mortals is discussed. It was a mind-blowing to Finrod, but he was receptive to the idea (like many Elves might not be).

In their debate, Finrod had asked:

Therefore I say to you, Andreth, what did ye do, ye Men, long ago in the dark? How did ye anger Eru? For otherwise all your tales are but dark dreams devised in a Dark Mind. Will you say what you know or have heard?

He doesn’t believe it remotely possible that Morgoth could shorten the lives of Men, but at least allows for the possibility that Ilúvatar could have done so as a punishment. He doesn’t understand how, which is why he presses to hear the tale. Andreth relents and tells it. And so here it is, or my version of it. And remember, this is secondhand information, since Andreth, in turn, was told this story by Adanel, who passed it down from her people’s lore-masters.

Let’s suppose it was presented as a kind of old-fashioned morality play. It might look something like this.

ADANEL’S TALE: A Play in One Act

Enter MEN (and women of the race of Men, of course).

Men: Look at us, we’re totally new. This is our beginning!

Other Men: Our origin story. And look, none of us have even died yet.

Other Men: Died? What are you even talking about?

Other Men: LOL, no idea. We don’t even have a language yet. We’re basically just miming things at this point.

Enter the VOICE.

VOICE: Listen up, all of you.

Men: Whoa, who are you? We hear you, though we can’t see you. You’re everywhere and yet right here, it seems. We’re listening!

VOICE: You are all my kids, and I put you here on Earth to live. In time, you’ll even be in charge of this place. But you’re still young and have much to learn first. Call to me; I will always hear you.

Men: And not even in a creepy way.

Other Men: We hear you in our hearts. But we’d love to use actual spoken words from our speaking mouths, so we’re going to have to invent some. Might take a while, since there aren’t that many of us yet, none of us are linguists, and this world is big and unfamiliar. We want to learn everything! Let’s get started.

VOICE: Exactly, that’s the idea.

* * * * *

Men: Well, we’re coming along, I guess. We’ve been calling for the Voice a lot, and it always responds, which is awesome. It really seems to care about us, but boy is it mysterious! Doesn’t always answer our questions.

VOICE: Right. I want you guys to find some answers on your own first. There is joy in discovery. It’s how you grow up, how you become wise. Don’t hurry, don’t try to skip steps or cut corners. There’s plenty of time.

Men: But we sure are impatient! We want to start making decisions about things before we properly even understand them. We can kinda sorta imagine how we want things to be. How about we do that! Maybe we don’t need to speak to the Voice so much, then?

* * * * *

Enter the GIVER OF GIFTS.

GIVER: What’s up?

Men: Whoa, who are you? We can actually see you. You look like us, but you’re…more remarkable and easier on the eyes.

GIVER: I came because I sympathize with you people. You’re basically unchaperoned. You shouldn’t have been left to figure things out on your own like this. The world is full of amazing wealth which you can access sooner rather than later, if you’ve got the know-how. You could have even more food than you’ve figured out how to get so far. Tastier, too. How about bigger homes? Would you like that? Way more comfortable ones, too, with, like, interior lighting and proper insulation. And you could even get ritzy togs like I’ve got.

Men: Yeah, your clothes are gilded and silvery! And look, you’re even wearing a crown! What are those little shiny stones in your hair?

GIVER: Pretty sweet, aren’t they? They’re called gems. If you like what you see, and want the things I’m talking about but without all the dicking around, then let me be your teacher.

Men: We’re hot for teacher!

GIVER: Exccccellent.

* * * * *

Men: So, umm, I really thought we’d be further along than this.

Other Men: He seems to be taking his time with the whole teaching thing, isn’t he?

Men: Yeah, we still have things we want to find or make. I have to say, all this waiting has only made us think up more things we want.

Enter the GIVER.

GIVER: Do not doubt me. Look, here are some of those things.

Men: Woo-hoo! Having things is great.

Other Men: Does anyone else notice he only seems to bring stuff when we get really antsy, though?

GIVER: Shush. I am the Giver of Gifts. Just keep trusting me and they’ll keep coming.

Men: The Giver of Gifts sure is swell. We should be totally deferential to him. Heck, we need him. No way would we have ever been able to get this much loot without him.

Other Men: Let’s not rock the boat. He’s our only way to maintain this swingin’ lifestyle, and there’s so much more to find out: animals, plants, how we were made, the Sun and the Moon, what those nighttime stars are all about, and all that spooky darkness in the sky behind them.

GIVER: Everything I teach you about is good, right? I know more than anyone. I know the best things. Everybody says so. And yes, let’s talk about that Dark up there. It’s the crème de la crème, that Darkness. It’s infinite! And I would know, it’s where I came from. In fact, I’m the master of the Dark, and I made the Sun and the Moon and all those stars that inhabit it. I will always protect you from the Dark, which otherwise would eat you up.

Men: That’s…not at all creepy.

Other Men: What about the Voice, though? Remember that, guys?

GIVER: NO. That was the voice of the Dark you heard. I’m its master, remember? It didn’t want me to come teach you things; it jealously wants you for its own appetite.

The GIVER leaves.

* * * * *

Men: So…why did the Giver of Gifts up and leave for such a long time?

Other Men: We feel rather…lacking. Empty now. Without the cool stuff the Giver brings us, we’re just not the same. Do we really have to go out and look for it ourselves?

Other Men: Also, what’s up with the Sun getting so dim? I mean, it’s really getting dark. Look, even the beasts and birds are quiet and afraid.

The GIVER approaches.

Men: Uh-oh! Everyone, eyes down! We shouldn’t anger him.

GIVER: Some of you are still listening to the Voice of the Dark, aren’t you? Ergo, the light is failing. Choose, you Men. Choose NOW. It’s me or the Dark. If you wish to have the Dark be your lord, so be it. There are plenty other places more worthy of my time. I certainly do not need you. Swear to serve me, or I shall go.

Men: We choose you. And only you. We will renounce that dumb old Voice and not listen to it anymore.

GIVER. Good. Now build me a temple somewhere high up, call it the House of the Lord. I will go there whenever I come to you. And you will call to Me and make your formal pleas to Me from there only.

* * * * *

Men: There, we’ve done it. And look, it’s lit! Even with fires, just like we think you wanted.

GIVER: Good. Now, if any of you still listen to the Voice of the Dark, come here before me.

None go forward.

GIVER: Did I stutter? Come before Me and bow. Name Me as your Lord.

All Men: You are the only one for us, Lord, Master, whatever you want. We are all Yours.

They bow.

GIVER: Behold my fire! [poof]

The GIVER disappears.

Men: Ouch, so hot! Wait…where did he go?

Other Men: And why is it so dark now? Let us flee this place!

* * * * *

Men: The Dark is still out there, above us, seeking us. It’s giving us the willies.

Other Men: Our Master isn’t coming by much anymore, either. And when he does, his gifts are slim pickings.

Other Men: We have gone into his House to pray to him, and we’ve heard him, but instead of giving gifts, he asks for gifts. From us. As payment! He wants us to…do things…to earn his attention.

Men: The things he commands us to do are not good things. And they’re getting worse.

* * * * *

Enter the VOICE.

VOICE: You have all renounced me, but you are still my children.

Men: Yay! The Voice is back!

Other Men: Uh-oh! The Voice is back!

VOICE: I put you here and gave you life. But you blew it. Now that life will be short, and each of you will return to Me in due time, and you will learn just who it is you’ve worshipped and called your Lord. (FYI, I made him, too.)

* * * * *

Men: Why has the Voice stopped speaking? Now we’re even more afraid of the Dark, since the Voice is the Voice of the Dark.

Other Men: Allegedly.

Other Men: And we look like shit. We’re starting to waste away here. Master, save us from this…death! We are afraid of that Darkness behind the stars.

Other Men: The Master doesn’t answer anymore, either. Maybe we should try pleading in the House.

Men go into the House.

Men: We have come here, Master. Save us from death! We bow down.

The GIVER enters.

GIVER: Well, look who’s come crawling back. Now you must do what I say. Remember, you are all Mine. What I don’t care about: that some of you are dying off, which feeds the Dark. Suits me just fine, since you’re multiplying on this Earth anyway, infesting it like bugs. Now, if you don’t do as I say, you will experience my wrath and die even sooner.

Men: Woe are we. Now we grow tired, and hungry, and sick. The Earth has turned against us. The elements, the flora, the fauna, all have become hostile to us. Even the shade of the trees, for crying out loud.

Other Men: If only we could go back to the time before the Master came.

Other Men: Shhh! We may hate him now, but he’s as scary as the Dark is. We just have to do what he says and keep our heads down.

Other Men: No, we’ve got to do more than what he says. We must regain his favor, no matter how evil our acts. At least maybe he won’t kill us that way?

Other Men: That’s not working so much.

Other Men: Speak for yourself. He shows some of us favor, we who are tougher and more ruthless and hang out in his House more often, worshipping. He still gives us gifts, and secret knowledge. We are more powerful than you. So we will command you as well!

Rebels Among Men: Yeah, well, at least we know who is the liar now. At least the Voice never wanted to kill us. But our Master, the so-called Giver of Gifts? He’s the Master of the Darkness; he lives in it. We will serve him no more. He is our Enemy.

Other Men: Then we will kill you, so that the Master doesn’t hear you saying these things and punish us all!

The rebels are hunted, and most are caught and dragged into the House and sacrificed in fire.

Other Men: That pleases the Master. He’s easing up on us a bit.

Other Men: Just a bit.

* * * * *

Other Men: Well, we got most of them, but some who resisted the Master have escaped us! They’ve fled into faraway lands. D’oh!

* * * * *

The Rebels Among Men: Well, we’ve gotten away, but we know the Voice is surely still angry with us, for we had bowed down to the Giver of Gifts, who is our Enemy.

Other Rebels Among Men: We’ve traveled far across the lands and now we’ve reached an insurmountable body of water. Can anyone swim?

Other Rebels Among Men: Well, crap. It turns out the Enemy is already here in this new realm before us.

Annnnd…scene! That’s it. Full stop. It’s where the Tale of Adanel ends.

For those familiar with The Silmarillion, those rebellious Men who finally resisted the Giver of Gifts go on to become the Elf-friends. Led by Beör the Old, they meet Finrod after crossing the Blue Mountains, which cheers them up. But then they got the bad news: that Shadow of evil they’d tried to put behind them was actually living in Beleriand the whole time (well, just north of it). Apparently, his stint as the Giver of Gifts was just a side hustle.

As recorded in “Of the Coming of Men Into the West,” some disgruntled Men said to themselves:

We took long roads, desiring to escape the perils of Middle-earth and the dark things that dwell there; for we heard that there was Light in the West. But now we learn that the Light is beyond the Sea. Thither we cannot come where the Gods dwell in bliss. Save one; for the Lord of the Dark is here before us…

As should be plain, the Disaster depicts a kind of “Kinslaying” moment for Mankind, not so coincidentally reminiscent of the Christian Fall of Man for the massive ripple effect it has on the race forever more. Not only did Men kill one another at the bidding of the Giver of Gifts—the so-called Lord and Master of the Darkness itself—they worshipped him. And the Voice! That is seemingly Eru Ilúvatar himself—an astonishing fact, if true, since while the mighty Valar have spoken with their creator firsthand, none of the Elves ever have.

Buy the Book

Hollow Empire

So this is what Andreth didn’t want to tell Finrod during their debate, the reason why mortals believe they die: because they refused to obey Eru, and in their impatience, laziness, and greed, they stooped to the worship of Morgoth himself. Now, are we to consider this event as having been “real” in the context of Tolkien’s secondary world? Is this what he was really working his way towards retconning? (As he did some other things.)

Not necessarily. For one, it challenges all the ideas about mortal death throughout the legendarium. It’s counter to what the Elves believe, and what the Valar, in turn, were told about them. And though neither Elves nor Men were made by the Valar—their spirits, bodies, and fates were exclusively an Ilúvatarian project—the Valar were still given great authority over life and death. If Ilúvatar intended Men to live forever, only to put the brakes on that early in their development, I think Manwë and Mandos, in the very least, would have been informed. And that would certainly have been taken into consideration in the whole Númenor event, wouldn’t it?

Then there’s simply the evidence that Tolkien puts forth. After the initial “debate” with Finrod, yet before the Tale of Adanel, he writes (in his own voice, not even through a narrator):

It is probable that Andreth was actually unwilling to say more. Partly by a kind of loyalty that restrained Men from revealing to the Elves all that they knew about the darkness in their past; partly because she felt unable to make up her own mind about the conflicting human traditions.

He goes on to say that the Edain had written accounts of Andreth’s convo with Finrod, and according to some of the ones “edited under Númenórean influence,” she did eventually relent and tell him Adanel’s tale “under pressure.” Of course, the way the Giver of Gifts tricks these mortals into doing his bidding, turning them against their divine creator in order to attain greater worldly power, sure sounds like what Sauron did as advisor to the last king of Númenor. Coincidence? Was that Sauron acting out of his old boss’s playbook, or is it just too on the nose? The downfall of Númenor and the story of Men’s fall might simply come from the same mythic tradition. How many real-world cultures have stories about dragons without obvious connections between them, after all?

Then there’s Morgoth himself. In The Silmarillion, when the Sun rose for that first time and Men awoke in the far east, Morgoth was already trapped in his wicked-looking Dark Lord persona because he’d squandered his power and was unable to “change his form, or walk unclad, as could his brethren.” In his old “tyrant of Utumno” get-up, Morgoth cannot appear as pretty as he is so often rendered in fan fiction. By the limits of his own misspent power, he cannot assume a form like the one described in the Tale of Adanel:

and lo! he was clad in raiment that shone like silver and gold, and he had a crown on his head, and gems in his hair.

Just gems? Regular ol’ shiny rocks? And the headpiece we’re talking about here would have to be the very “great crown of iron” he’d forged for himself, set the three stolen Silmarils in, and that “he never took from his head, though its weight became a deadly weariness.” I’d think it would be hard to conceal this, even for him. Those Silmarils shine like the dickens! That’s kind of their whole deal.

So what’s the alternative? Was the Giver of Gifts still somehow Morgoth, or are we to believe he was hiding out in the bushes like Cyrano de Bergerac, whispering to some good-looking proxy and telling him what to say? We know he employs plenty of “shadows and evil spirits” throughout The Silmarillion, who engage in all kinds of espionage schemes. But would one of these lesser beings really be up to the task of corrupting the Secondborn of the Children of Ilúvatar on his behalf?

In theory, the Giver could even have been Sauron, right? Maybe Morgoth brought him along on his road trip to the far east. Though he was Morgoth’s lieutenant at the time, Sauron was perfectly capable of fair-featured, silver-tongued deception at this point in time, in terms of sheer power. But if Sauron played such a crucial role, corrupting the Secondborn and getting them saddled with the fate of death forever, that sure seems like a bigger deal than anything he’s associated with later. Including the Rings of Power. The Fall of Man would definitely have gone on his résumé, is what I’m saying.

So yeah, points and counterpoints abound. Elsewhere in Morgoth’s Ring, Christopher Tolkien shares another deleted scene concerning that time when Melkor/Morgoth goes to recruit Ungoliant(e), the gigantic primordial arachnid who was weaving webs in mountain clefts before it was cool. When she doesn’t come out to greet him, Melkor scolds her:

‘Come forth!’ he said. ‘Thrice fool: to leave me first, to dwell here languishing within reach of feasts untold, and now to shun me, Giver of Gifts, thy only hope! Come forth and see! I have brought thee an earnest of greater bounty to follow.’

Now, is it just a coincidence that Morgoth calls himself the Giver of Gifts here? Maybe he was just been workshopping that title, throwing it at a web to see if it sticks? If it works on an unfathomably evil giant spider, surely it will work on measly mortal bipeds! Hmm. Does coming up with a grandiose epithet only to drop it onto some lowly henchman sound like something Morgoth would do? And I must say, the corruption of Men through lies and alternative facts feels like it’s got that personal Melkor touch to me. Interestingly, but maybe not surprisingly, it’s worth remembering that when Morgoth is taken out of the picture in the Second Age, Sauron calls himself Annatar, the Lord of Gifts, when conning Celebrimbor and the Elves of Eregion.

Of course, even if Morgoth didn’t show up in person to coerce Men into worshipping him, there is one thing we know he did succeed with. Per The Silmarillion:

Death is their fate, the gift of Ilúvatar, which as Time wears even the Powers shall envy. But Melkor has cast his shadow upon it, and confounded it with darkness, and brought forth evil out of good, and fear out of hope.

Which is to say, death for mortals was never supposed to be a punishment, nor even seen as one. Only a sorrow, maybe, that is more like a parting before the next meeting. But Morgoth spoiled it. Pissed all over it. Made it scary and gross. Made it fearful. Got mortals all worked up over it so that it becomes a defining part of their culture. With wisdom, some of the Edain in later days do come to understand it…better, if not completely. The early kings of Númenor hand off their scepters to their successors and surrender peaceably to death without a fuss. Even Aragorn eventually does at the end of his long life. There is still mourning in the event, but there is also acceptance.

From Appendix A of The Lord of the Rings, King Elessar tells his wife, Arwen:

Nay, lady, I am the last of the Númenóreans and the latest King of the Elder Days; and to me has been given not only a span of thrice that of Men of Middle-earth, but also the grace to go at my will, and give back the gift. Now, therefore, I will sleep.

No, I don’t think Tolkien was preparing to throw Aragorn under the bus of revision and make false his deathbed words.

Andreth believed that the Shadow—Morgoth himself—imposed death on Men and that the Valar and the Elves simply couldn’t stop it. She felt Men were wronged. Yet Adanel’s tale places the wrongdoing on Men for the sins of worshipping a false god. There was shame in the story; hence it was kept mum. But there was also some blame given, if indirectly, to Ilúvatar; the tale suggests that for Men’s disobedience he changed their fates forever.

Yet for all its disjointed place in the legendarium, I appreciate that we have this account of the Disaster. Whatever its validity, the story resonates. It’s familiar. Maybe too familiar. It gives weight to Andreth’s bitterness and the human condition—whether there is truth in it or not, it places Tolkien’s “gift of death” at odds with humanity’s expectations. Or at least with its desires. No matter what, things weren’t going to add up smoothly for Men (or anyone), because this is still Arda Marred. Ilúvatar isn’t going to simply unmar it. That’s not his style. He allows the marring, and then uses its consequences for the betterment of all, “in the devising of things more wonderful.” Wisdom from sorrow.

Tolkien might have been considering the truth of the matter, or he might simply have been doing what he did with a lot of his writing after The Lord of the Rings: filling in the many, many gaps. Not just stories about what happened in the Elder Days of Middle-earth but the stories that its inhabitants told, factual or not. That’s what makes the legendarium so rich, so believable. Had Tolkien actually gone on to make the Disaster canon, then to me, it wouldn’t be as compelling. It upends his way-cooler concept of death as a gift—a release from the evils of Arda Marred. With this, death is a springboard to some other unguessable destiny.

But let’s not mistake acceptance of death for Men (when it comes) as Tolkien green-lighting suicide. Far from it—the characters in Middle-earth who take their own lives directly are making tragic choices. Túrin’s final act isn’t courageous, it’s despairing. Denethor’s hopelessness and self-made pyre play right into Sauron’s hands. Even Éowyn tells Faramir that she “looked for death in battle,” but Aragorn calls even that part of her “malady,” and in the aftermath her heart and mind find healing. To quote the words of another Tolkien fan (going way back), and a hero of mine, whose passing early this year is still a sadness of its own:

All of us get lost in the darkness

Dreamers learn to steer by the stars

All of us do time in the gutter

Dreamers turn to look at the carsTurn around and turn around and turn around

Turn around and walk the razor’s edge

Don’t turn your back

And slam the door on me

Mortality seems to be natural for Men, but that doesn’t mean they—err, we—aren’t in many ways shortchanged. Even Finrod conceded that to Andreth. Death might come sooner than it should. We fear it, we even perceive it as unnatural, as though it’s some mistake. That’s part of the marring, and Morgoth—and sometimes humanity’s poor decisions—can rightly be held to blame for that. I can’t imagine any real-world belief system that wouldn’t regard death by accident, sickness, or violence as “an unjustifiable violation,” anyway. Simone de Beauvoir called it. The hope is for the rest of us to keep moving forward in spite of this, to seek the wisdom and compassion left in its wake.

After all, as Aragorn says much earlier in his life, when there was still a Dark Lord to fight, “We have a long road, and much to do.”

Top image from “Fog on the Barrow-downs” by Jonathan Guzi.

Jeff LaSala knows quoting Rush might seem like a deviation from Tolkien but assures you it isn’t. He can’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone and is unapologetically responsible for the The Silmarillion Primer, He also wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He sometimes sputters about on Twitter.

It’s meme time: Anatar, Lord of GIFs

I would have been disappointed if mentioning gifts didn’t summon you, Dr. Thanatos. ;)

Anatar does have a gift-card program; it’s for frequent fliers and he currently has 9 participants

I think that a few of the discrepancies indicate that it was intended to follow his Myths Transformed conception – where the Sun and Moon existed from the start, and the birth of Men was pushed back further in time.

I, personally, don’t like that shift (it makes a lot of the Trees and Light stuff less special), but that would fit with Melkor coming to Men before the Fall of the Trees, and thus still able to change shape and without the Silmarils.

@@.-@ Right. In some ways it’s all part of a bigger conversation: that Tolkien’s pondering of reworking some cosmic circumstances would have involved tinkering at all levels. And that may be the why it doesn’t fit neatly. And I do agree with you: I also like the Lamps, and the Trees, preceding the Sun and Moon. It makes this mythology so much more original than other worlds.

OP: He’d been shown the door—literally kicked out of the solar system—by his former peers.

Was it as small a space as the solar system? Or was it out of all of Arda, which was all of creation, wasn’t it?

@6, well, Morgoth is kicked out of Arda for sure (which is what’s most relevant here). Through the Door of Night and into the Void itself. That does imply, perhaps, that he’s exiled from Eä (the universe) itself, right? If you’re in Eä, you’re not in the Void. So yes, it might be more technical to say that Morgoth was ousted from all of Eä; kind of makes me think he’s shot through some kind of worm-hole from the Doors of Night to the outer edge of Eä, but then I’m thinking about this very spatially. I’m not sure Tolkien’s universe requires that kind of thinking. I’m not sure it’s 100% clear, but now I’m going to look into it again.

Arda is still quite big, though. We tend to think of it as the planet itself, but it is more than that. It’s also the “upper airs” of Ilmen, and the Firmament, under which the Sun and Moon sweep through. This has to mean Arda alone still includes a huge swath of stars and other celestial bodies.

Oh, look, I had worked up a visual for the end of the War of Wrath:

@7: Well, that was kinda my point . . . that he was kicked out of more than, or greater than, the limits of the solar system itself.

For some reason while reading this, I keep thinking back to the Dresden Files and Uriel’s repeated presence as the protector of Free Will for the creator. Much the same way for Tolkien – that free will is the grace we get to make up for the price we pay.

I feel like the story that Adanel tells isn’t incompatible with the Silmarilion timeline and philosophy if you consider that men ARE mortal and have always been and the story of the Disaster would have happened many generations before. So I’d like to think that Melkor indeed came to mankind in the beginning and provided answers and wealth and was worshiped by some who were willing to harm others and spread his lies and might have the wealth and arms to amass more support. I’m sure that, even as terrifying as Melkor might have looked, it would have been easy to point a finger at Eru at the source of their mortality as well as Melkor’s own monstrous visage as a punishment. Over generations it would be so easy for the heavy hand of Melkor to get followers to spread the lies that men did “something” to piss off Eru but that he could maybe liberate them. And while I don’t remember the Silmarilion ever saying specifically that a kinslaying of men happened it would certainly explain the split and thus further compounding the lie of death as a punishment.

By no means does this downplay the wisdom and knowledge of Adanel but if we’re talking of hundreds or even a thousand years of orally taught history information gets lost in the shuffle

I wonder if it would help to take a more figurative interpretation of Morgoth’s appearance. Maybe he didn’t lose the ability to physically transform into a conventionally attractive, human-like being. Maybe it’s that, after the killing of the Trees and the rape of the Silmarils, his sin was written on his face for all to see it who could. I’ve read novels where, if a man commits murder, people with experience and insight can see it in the man’s face. Maybe Melkor lost the ability to appear wise and gentle in the eyes of the Eldar, but he could still fool Men while they were in the infancy of their race.

I’m astounded that Tolkien read — or at least, had read some of — Simone de Beauvoir. Do you have a link for the film where he’s “reading it aloud”?

It might be overstating to say he’s was an all-out fan or anything. Here’s one such:

https://youtu.be/Z8ruXLSWXwc

JLaSala@13 — thanks for the link! It’s funny, I just never think of him as even being aware of anything outside of Old Norse and suchlike, but of course that’s silly of me.

While Tolkien’s view of death as a gift helps make the legendarium so unique, it’s interesting because Tolkien is a devout Catholic, which views death even worse than Adanel… a very clear curse due to Man’s disobedience to at from the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.

Finrod: Death is the Gift of Eru to Men

Andreth: I TOLD them to keep the receipt…

I wonder what are the implications of Aragorn’s statement that he was giving the gift back. I get that it is a way of saying that he was going to die, but does that mean the enter into Ilu’s presence?

@17 Dan,

I took this to mean that he was refusing to repeat the error of his ancestors and cling to life.

“I am giving the gift back instead of holding on to it as tight as I can until it is ripped from my hands”

Yeah, I think Dr. Thanatos has it right. The Gift of Death is what some call it, but it could just as well be called the Gift of Being In the World Only a Short Space of time. Like a hall pass for Arda. Aragorn’s time of holding onto it, and being active in the world, is up, so he’ll return it to the one who gave it to him. He won’t try to hang onto that hall pass indefinitely to go and smoke in the bathroom (like those latter-day Númenóreans).

Even in Christianity death can have a dual meaning/be redeemed though. I don’t know how exactly that fits into Tolkien’s legendarium.

Although I appreciate that he didn’t make it a carbon copy – I can’t recall if you wrote about this in the Artrabeth but I believe there were also some musings on an incarnate Eru that was maybe a little too on the nose.

@7 i’ve always wondered when Morgoth is booted out through the Door of Night, is he still bound to the World even in the Void? Can he travel to other realities, or is he still on the periphery banging on the Walls?

All of these essays and stories that Tolkien wrote to help him think about his own creation are fascinating to me. That he cared so deeply about it that he wanted to make this as consistent as possible with both his own beliefs, and with the ‘real world.’

This story itself, with Morgoth as the “Giver of Gifts,” makes me feel that humans didn’t quite understand their own nature. And that perhaps death was much further off than what happened. Perhaps the expanded life of the Numenorians was what humans were *supposed* to have in the first place, but was then lost because of their deception at the hands of Morgoth/Sauron/Pretty Balrog.

Either way, I’m happy to have these bits and bobs to read, as it continually amazes me how Tolkien thought about his own creations.

Im lost a bit. Maybe I am reading it wrong but I always seen it that humans where mortal by design. Melkor didnt change that (if indeed this tale has truth to it) but his early days meddling made Eru shorten their lifespan compare to originally intended.